While many people in Washington are continuing to experience financial abundance, data illustrates that too many state residents still struggle to pay for housing, food, and other basic needs. Recently, the U.S. Census Bureau and the Center on Women’s Welfare at the University of Washington released updated poverty data. While the agencies use different measurements of poverty, the findings in both cases nevertheless make it clear that lawmakers must do more to support low-income households.

As a note about the data: Given that policymakers routinely rely on data from the Census, it’s important to keep track of it while also recognizing that it routinely fails to capture the scope of poverty across the nation. It doesn’t reflect the true number of people struggling to make ends meet. The Center on Women’s Welfare created the Self-Sufficiency Standard to augment the Census’ findings. The Self-Sufficiency Standard determines the annual income necessary for a household to meet their basic needs. Unlike the Census’ official poverty measure, the Standard calculates the cost of living and living wages by considering differences in family composition, ages of children, and geography.

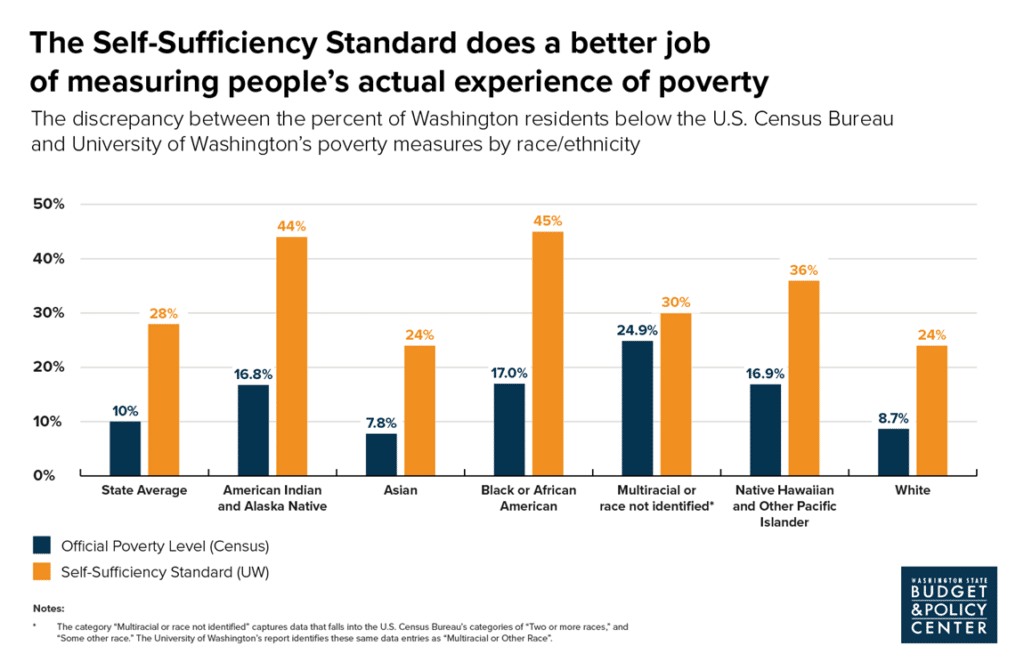

Anti-poverty policies and programs strengthened throughout the COVID-19 pandemic drove the child poverty rate to a record low in 2021. Share on XAccording to the Census data, in Washington, 754,315 people, or roughly 9.9% of the population, fall below the federal poverty threshold.1 (That translates to $14,880 for a single person or $29,950 for a household of four.2) Building on that data with a more comprehensive measure of living wages, the University of Washington’s report suggests that nearly three times (28%) as many Washingtonians struggle to make ends meet.3 Both the Census and University of Washington’s findings indicate that too many households in Washington cannot keep up with the rising costs of living.

Inequitable policies have created disproportionate impacts of poverty by race

Centuries of racial discrimination in employment, housing, education, and other institutions and policies contribute to ongoing income disparities among Washingtonians of different races. For example, according to the Census, in Washington, white people are half (8.7%) as likely as Black (17%), American Indian and Alaska Native (16.8%), and Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander (16.9%) people to experience poverty.4 The University of Washington’s data paints a more dire picture. According to their report, nearly half of Black, American Indian, and Latinx households struggle to make ends meet in Washington, while 24% of white households fall below the Self-Sufficiency Standard.5

Click on graphic to enlarge

Changes in the child poverty rate reveal the impacts of anti-poverty policies

Childhood poverty has both immediate- and long-term ramifications on the health and well-being of young people. It can lead to impaired cognitive and emotional development, behavioral issues, a lack of school readiness, and an increased likelihood for people to experience poverty into adulthood.6 According to the Census data, one in four Washingtonians experiencing poverty are children. Furthermore, the University of Washington finds that nearly half of households struggling to meet basic needs are those with children.7 In 2022, the national child poverty rate (12.6%) more than doubled after hitting a record low (5.2%) in 2021.8

A positive development in recent years is that anti-poverty policies and programs strengthened throughout the COVID-19 pandemic drove the child poverty rate to a record low in 2021. The expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC) – with higher credit amounts, broadened eligibility criteria, and increased accessibility measures – reached over 61 million children in over 36 million households. 9 In Washington, the expanded CTC resulted in a 40% one-year reduction of the child poverty rate, lifting nearly 70,000 children out of poverty.10 Anti-poverty programs directed at children, like the expanded CTC, not only have a meaningful impact today but can reduce poverty rates for decades to come.

Lawmakers can bring economic security to hundreds of thousands of households

The success of the federal CTC demonstrates that direct cash support to families with low incomes has the power to substantially reduce poverty rates. Further, in Washington, we’ve had some important direct-cash wins in recent years – with the COVID-19 Immigrant Relief Fund that lasted throughout the pandemic and the passage of the Working Families Tax Credit (WFTC) in 2021. Now, we have the power to do even more to ensure that fewer households experience poverty. Lawmakers can strengthen several existing and prospective programs to further reduce poverty rates across the state:

- The Working Families Tax Credit – Launched in 2023, the WFTC provides annual cash payments of up to $1,200 to over 400,000 Washingtonians with low and moderate incomes. In the 2024 legislative session, lawmakers can make the program more inclusive by loosening the age restrictions so anyone older than 18 can qualify.

- The Washington Future Fund – This prospective program would supply all babies enrolled in Apple Health before their first birthday* with a $4,000 investment to be withdrawn for specific wealth-building activities between the ages of 18 and 36. The fund ensures that all children in Washington can build sustainable economic security – chipping away at the racial wealth gap.

- A statewide Guaranteed Basic Income (GBI) – In 2023, lawmakers proposed establishing a statewide GBI pilot that would provide regular, unrestricted, unconditional cash benefits to households with low or moderate incomes. The pilot has the potential to develop a more inclusive and robust state economy.

While the data differs according to how it is measured, one thing is clear: poverty persists throughout Washington at alarming rates – particularly in non-white households. Not only should everyone be able to meet their basic needs, but they should also have the opportunity to prosper and save for a rainy day. This legislative session, lawmakers must fortify and enact state programs to alleviate poverty for hundreds of thousands of households. Decision makers must also consider using more expansive data sets that better reflect the lived realities of all state residents.11